After being sick recently, I was reminded of some of my fever dreamish memories from when I was a child. Ones where I’m half asleep on the couch and I can feel my mother’s cool hand gently lay on my forehead. I can hear the vibrant sonics of her voice warm the space in the air, “Oh honey, you’re burning up”. The words, not necessarily slower or staccato, but grew that way— as my ill-ravished brain tried to fill in the gaps between its senses and its fatigued state. Where as any visuals recalled are blot out more like a half turned-on light in the hallway. Vocal tonality has always been very resonant to me. I think this might be the origin as to where I can first recall preferring sound over any of my other senses. When my girlfriend calls me on the phone— her voice is what I want to hear first. I find myself often refraining from saying hello, before I hear hers first. Her voice is currently my favorite sound. Her southern California accent imbued with intonation of a Mid-West hat tip makes it a bit unique (and more soothing) for my Boston-born ears, and, as always, it feels a lot like safety. I often think of her voice, or that of any comforting voice, the sonic impression of enclosure— like how right before first snowfall, the outside feels like an entire room.

Working on Little Mirror recently, we discussed the potential of putting together and publishing a folio of written work dedicated or adjacent to the late British poet Sean Bonney. Bonney was a radical leftist poet that had a big growl. His work was brash, angry, complex, bombastic, poignant, deeply undelicate, and incredibly smart. It makes a relentless reading experience. I was dug up a response I wrote as part of reading Bonney’s book Letters Against The Firmament. While there are a trillion things to talk about in that book, Bonney’s deforming (and a bit demented) epistolary poems perform in crazy sonic registers. These open letters to the broader poetry community are about all the fucked up race and class bullshit happening in Britain (and let’s face it, since the start of the empire). I was deeply compelled by the constant reference to how we are all cued into something called the global harmonics— the global hum, and I couldn’t help but think about “why song?” as the collective representation of unity, and truly what sound meant as a poet, and the transference of how sound renders our material reality. This an excerpt from what I explored partially about sound in my Bonney essays:

We are always compressing infinities of light with lens, sound through waves, shape– through a circle. We are always compressing the infinity of intangibilities through speech. Through sound. Photography is always how I’ve been able to render this concept, but Bonney’s propensity of the “global harmonic”– sound evoking the likeness of Lorca’s Duende and Nathaniel Mackey’s exploration of Cante Moro, that this deep song is recognized in spanish culture. Mackey writes that the concept of Cante Moro “bespeaks the presence and persistence of the otherwise excluded, the otherwise expelled” and makes space for the unimagined. Bonney renders the choral attributions to a deeper global hum, the forces of history and future married and furnishing the present – it’s deeper than the image. The image is above us, an exterior property, that sound is a more interior force, more possessive than an image. Sonics are a form of physicality, the burning hum of rage that is material. In reality, it’s the music that we are dealing with, not what's actually visible.

You cannot separate the conception of sound from Federico García Lorca’s Theory and Play of The Duende. Lorca was a gay communist surrealist poet living in Franco’s Spain (so you can imagine how well that went over). He was also known for getting friend-zoned by Salvador Dalí. Though FGL couldn’t bring on the heat with Dalí, he sure cooked with this one. Duende, is a spanish word or turn-of-phrasing for ghost, goblin, or spirit. Lorca discusses about how in true art, the artist cannot hold pure technical talent with no duende, or else the art falls flat. It is non-convincing. Duende is the dark sounds that come from the production and performance of art. As Lorca puts it directly in the essay, “it’s a mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher can explain” (Lorca, Theory and Play of The Duende).

Lorca goes on to describe what duende is and isn’t in classic poetic undertakings. He says something interesting about how duende doesn't arrive unless there’s the possibility of death— which to me, renders the risk of the art in the body— that there’s something internal on the line that’s about to give, and that the performance comes so close up to expelling it. We watch the performer on a tight rope sway and swing close to death, but it's that particular space that produces duende. I think if you’re someone curious about art or an artist yourself, Lorca’s essay on Duende is an absolutely essential text to read. Here’s another beautiful run I think about often from this piece:

Seeking the duende, there is neither map nor discipline. We only know it burns the blood like powdered glass, that it exhausts, rejects all the sweet geometry we understand, that it shatters styles and makes Goya, master of the greys, silvers and pinks of the finest English art, paint with his knees and fists in terrible bitumen blacks, or strips Mossèn Cinto Verdaguer stark naked in the cold of the Pyrenees, or sends Jorge Manrique to wait for death in the wastes of Ocaña, or clothes Rimbaud’s delicate body in a saltimbanque’s costume, or gives the Comte de Lautréamont the eyes of a dead fish, at dawn, on the boulevard. - Federico Garcia Lorca, Theory and Play of The Duende

Said like a true poet. Forever striving to reject sweet geometry. The notion of duende hugs tight to sound. As Lorca derives his concept from the spanish traditional folksong and flamenco. Last spring, I wrote an essay on post-punk’s relationship to jazz music and the beat poets, and, as a case for melodrama and duende. As an example of duende, I cited Bob Kaufman’s poetry and Black Country, New Road’s, former frontman, Isaac Wood, for conjuring the sonic forms of duende I believe Lorca was talking about. The breaking point in both these artists seem well earned, and yet so raw. Isaac Wood splintering at the end of Basketball Shoes at Queen Elizabeth Hall might be one of the most duende induced performances I’ve think I’ve seen my lifetime. Any one of us probably have a reference to where we see and hear duende in our own listening lives, or maybe experience duende in our own performances (any musicians out there? any poets?). This live performance of Nina Simone’s Be My Husband is another highlight of duende’s pertinence for me— the wobble of Simone’s voice is completely un-replicable. I also think of Nirvana’s famous live album MTV Unplugged in New York (1993) to be filled and riddled with the haunted rawness of duende. Maybe there’s the retroactive overhang with the unfortunate death of Kurt Cobain roughly six months after the release, but as many critics would agree— there was something uniquely profound and raw about this live set.

American musician, Ethel Cain, uploaded a video on her youtube channel called “the ring, the great dark, and the proximity to god” describing the transcendent state songs bring and walks us through her theory on how it functions. In summary, Cain explains mostly from a music production perspective, but also as a listener, that a song is like a ring: that if all the sonic lows, mids, and highs function correctly together in harmony, the ring can open up a portal into the Divine Theater. Which to Cain, is the state of transcendence, and where God is. In the Divine Theater, you never actually touch God but, Cain argues that the state of transcendence is only achieved by being in the presence of the divine, but not actually every reaching it. That in the Divine Theater, you brush up against the curtain of God before coming down and getting recasted into The Great Dark— which Cain describes as just the everyday life and existence we all inhabit. Before watching this video, my girlfriend was explaining this whole concept to me in the car and I teased that it sounds like Ethel Cain had just repackaged the concept of Lorca’s duende into an americanized mythos. And after watching it, I see that it’s not entirely the same. Duende more so deals with the sound within, while Cain outsources transcendence to external objects that serve as portals into the state of the divine. Cain goes on to elaborate about the dangers of the divine, staying in “the hole” and falling into “the maze” and never returning, which is so true, and something that perhaps we could suggest happens to a lot of artists. Both have a lot to say about the “near death” threshold being a sublime state of existence, and both use sound as their vehicle to wager their theories.

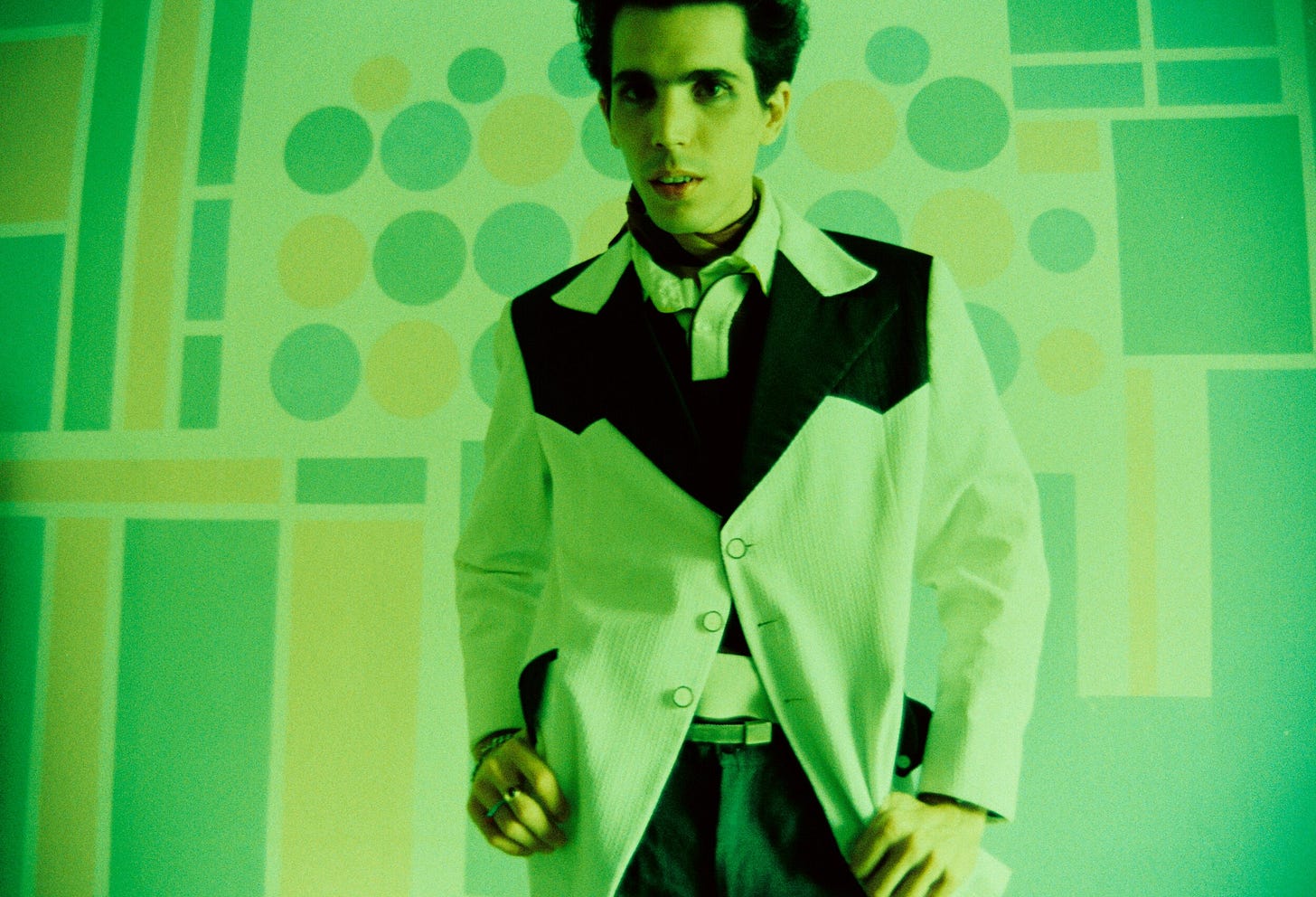

Another artist I love to point to that I think illustrates duende is Charlie Megira. Megira is an Israeli-born experimental guitarist who very much felt like an outsider in terms of understanding himself and his country’s government. Megira combines experimental licks and riffs, shoegaze, 50s rock and roll, ambient, jazz, and garage rock in the most compressed and expansive ways. Megira, who sadly took his own life in 2016, is still much of an unknown figure in music, and leaves behind very little aside from music, a couple interviews, and small documentary called Tomorrow’s Gone (2019) by Boaz Goldberg, after one of Megira’s most well loved tracks with the same title. The Record label, Numero Group, reissued most of his known discography in 2021 under the same title, Tomorrow’s Gone. The range of Megira is impressive, to the raw endless thrashing to the gentle procured ambient plucking of his guitar. Although, all Megira’s vocals feel shuffled and cryptic, a bit bent and haunted, but so explosive. He performs the freaky Elvis derived outsider really well. His song Elvis is Not Dead and Fear and Joy leach out the true freakadelic peaks of duende for me. The truths to life as I see it. Megira’s music will always reach beyond music for me— his work is truly an important representation of the delights and the haunted heaviness that identity disorientation and seeking contains. That any artist feels perhaps in micro and macro ways.

What dawned on me while reading Bonney (that man was duende-filled) is that we are constantly looking at images and visuals all the time. Visual culture has almost become pornographic, (and maybe always was from its conception). We are so elbows deep in the “infographic” era of the internet, and especially, as a means of political and collective communication. Bonney seems to be really frustrated with the lack of materiality in political action… which we could endlessly debate what art’s true political efficacy actually is and what that looks like in the material world. But visual objects to me are pretty much reliant on temporary encounters. They rely on the dependency of sight, and are only built back from a replica— of memory. I wouldn’t go as far to say that they are non-material (that would be exclusionary to photographs, films, and visual art that carry around the weight of the image). Saul Leiter’s work, pictured above, has a lot to do with the realistic tensions, compressions, and real life represented in visual art— but that there’s a certain intangibility with visual images that I think sound is truly the inverse of. The visual is always an external experience our brains make a process of. Whereas, sound are physical waves that vibrate and travel into and against our bodies. I recently saw The Zone of Interest directed by Johnathan Glazer and besides its stunning visuals and performances, the horrors of the holocaust are depicted are almost entirely through sound design. The juxtaposition between the bright pastoral imagery with screams and cries for help as constant background noise does so much work for me as a viewer. In a way, I felt the horrors more vividly than other holocaust movies I’ve seen. I see this as another example as to which sound seeps into my body and stays. This physicality and resonance sound imposes makes sense as to why Bonney is fixated on the global harmonic as the binding force that connects us all— and a primary metaphor that carries throughout Letters Against The Firmament.

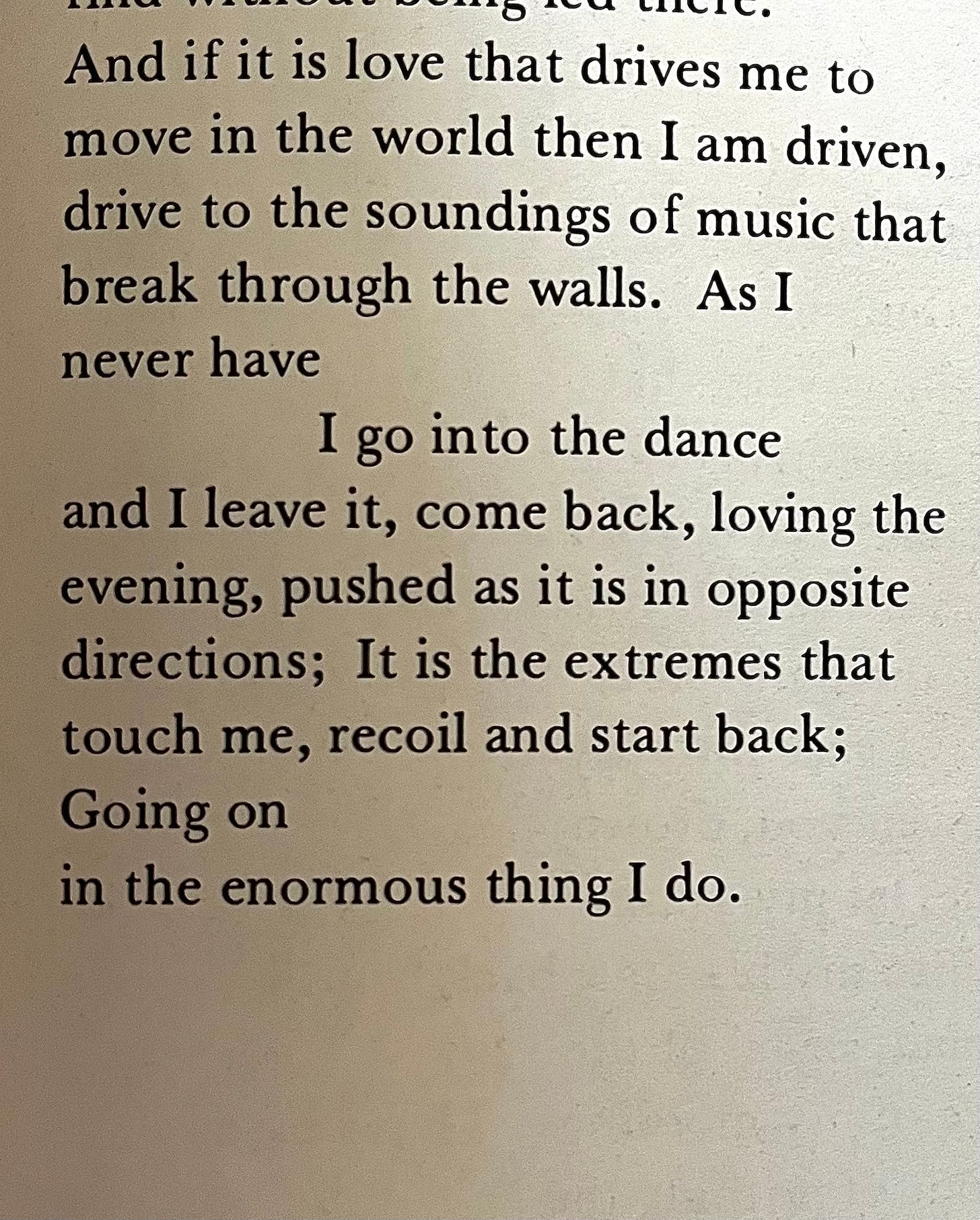

And maybe this is why arts that have to do with sound have come the most natural and emotionally for me to create and engage with. Because they are entirely possessive. There’s something truly indescribable about how it feels to pick up my guitar for five, maybe ten minutes, and engage in the act of sound production from my fingers to vibrations in my ear. What a magical loop! And, how listening to Damien Rice’s Accidental Babies on a walk will almost certainly bring me to tears before the end of its six minute and thirty four second run time. Last night, I was watching a live KEXP set of Jay Som’s Peace Out and was reminded of why guitar has been so important to my development as a poet. The gutteral-ness of Som’s guitar and the accompanied guitarist dips into a deep register of the true song during the bridge and outro-chorus. It clings in a way to sonic desire that I feel closest to in my poetic production. This intense adherence to hugging sound and rhythm. I would say the poet Charles Olson’s Projective Verse essay captures an umbrella-full of my philosophies of how a line should contain kinetic energy and break with freedom of breath. That a line’s most important duty is to conduct the sonic and musicality of language in a raw and real way to create its meaning. Even though I think Olson failed most oftentimes in his own work, his peers and predecessors Robert Creeley, (later) George Oppen, James Schuyler, Lisa Jarnot, Bernadette Mayer, Alice Notley, Eileen Myles (there’s many more to name) for example, really key into it. It’s what makes poetry work for me, especially in its orality. Like in this section of the poem Prayer to My Emblems from another favorite 80s fringe lesbian poet of mine, Alexandra Grilikhes:

I mean, the breakage of the lines do most of the work here, the fragmentation and attention to breath is masterful. “Going on/ in the enormous thing I do” reminds me of a Lisa Jarnot line from her poem Ode “for that he is the rest of the balance continuing huge.” Both these lines kind of send off into the infinity with the propulsion of the poem behind them.

There’s been music I’ve been listening to recently that give me the feeling that there are pieces of the sky falling in front of me, that poke into the global hum. I want to link this Spotify Playlist I made for more of how I’ve recently been seeing the function of duende and kinetics in what I’ve been listening to. But, One song I want to highlight is Souvenir by Orchestral Maneuvers in The Dark, (OMITD) whose music video functions as intense 80s summer nostalgia.

I feel as though OMITD’s serves sonically as a huge undercurrent and perhaps a souce of sponsorship to the “80s throw back” and ethereal soundscaping that has grown popular in our pop music today. I like to think of them as Beach House before Beach House, they got that Tears before Fears-y rizz. That whimsical sky gazing music that feels at all times breathly and cinematic. But the synths that background the track in Souvenir really poke out that sky fall feeling, and showcase the touring nature of the present, as today’s listener lusts back for the past. To me this is just as emotionally moving as more bombastic Isaac Wood’s devastating vocals, or Megira’s bucking and rowdy guitar.

I’d like to leave you this month with a sentiment my friend Holly Coté articulated to me this morning. She was thinking about how deeply beautiful birds are on her walk over to the coffee shop we met up at today. That they are these cute little creatures that are somewhat alien-like, meant to bring us song. Birdsong to me as a poet is a deeply important, and as CAConrad once said in my workshop class, birds are the oldest poets. We should listen in to them more. I hope to go birdwatching once before April. Birds, a kind and gentle part of the global harmonic, the earth’s deep song.